Listen here on Spotify | Listen here on Apple Podcast

Episode released on July 27, 2023

Mohammad Shamsudduha, known as Shams, is an Associate Professor at the Institute for Risk & Disaster Reduction at University College London. His research focuses on Earth’s freshwater resources, water risks and resilience, hydrometeorological and climatological hazards, and sustainable development with a special geographic focus on the Global South.

Mohammad Shamsudduha, known as Shams, is an Associate Professor at the Institute for Risk & Disaster Reduction at University College London. His research focuses on Earth’s freshwater resources, water risks and resilience, hydrometeorological and climatological hazards, and sustainable development with a special geographic focus on the Global South.

Highlights | Transcript

- Bangladesh has a population of 168 million people with an area of ~ 150,000 km2, similar to the size of Iowa state in the United States. Water and food security are critical issues in the country.

- The Bengal Water Machine, described in a recent Science paper, refers to groundwater pumpage for irrigation during the dry season, which lowers the water table, creating space for increased recharge during monsoon rains.

- The Bengal Water Machine increases food security by allowing 2nd and 3rd crops of rice during the dry season and reduces monsoon flooding. Bangladesh is the 4th largest producer of rice globally.

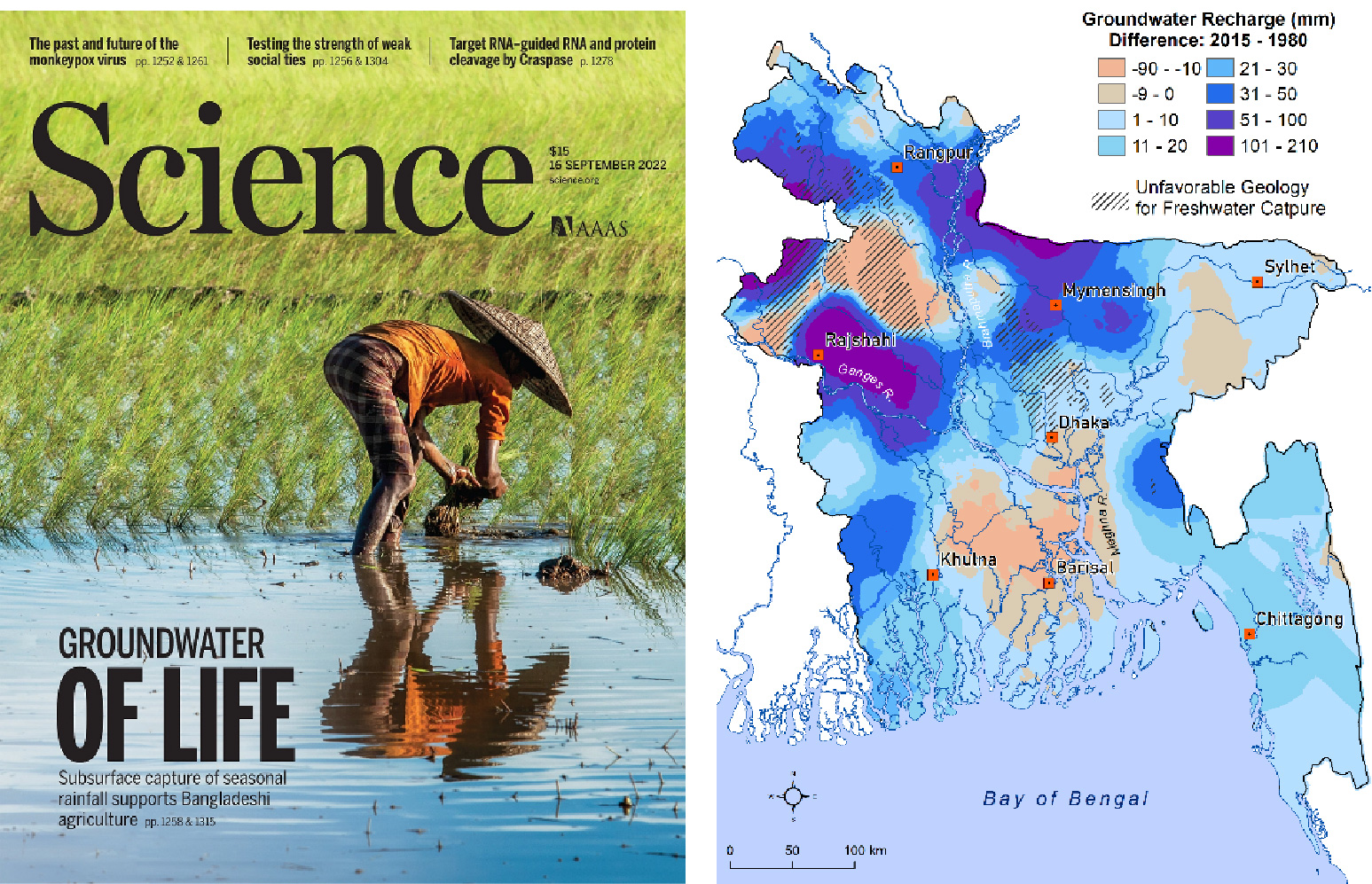

- The machine works in areas where soils are coarser and more permeable, more in the northwestern part of the country (fig. 1). Some other regions, such as the capital (Dhaka) experience groundwater depletion because of the high water demand.

- The concept of a water machine was first proposed by Revelle and Lakshminaryana in the mid 1970s when they discussed the Ganges Water Machine in a Science paper.

- Water quality is also a critical issue in Bangladesh. In the 1970s and 1980s Bangladesh and India switched from mostly surface water to groundwater because of widespread fecal contamination of surface water and related diarrheal diseases.

They found that groundwater quality was affected by high levels of arsenic with concentrations exceeding 10 to 15 times the World Health Organization standard of 10 μg/L or Bangladesh standard of 50 μg/L. - The largest mass poisoning in the world is happening in India and Bangladesh, resulting in skin lesions and cancer with the discovery of tubewell drinking water in 1983 but took about 10 years to be widely recognized.

- High levels of arsenic are mostly restricted to the shallow zone (≤ 30 – 50 m deep) in southcentral Bangladesh. If groundwater pumping is mostly restricted to the shallow zone and limited pumping for drinking water and municipal water use in the deeper zone, deep groundwater should provide arsenic free water for the next 100 years based on modeling analyses.

- Shams’ work also looks at linkages between groundwater quality and health. In addition to arsenic impacts, his work on high salinity groundwater (>1000 mg/L Total Dissolved Solids) in coastal areas has been linked to high blood pressure and preeclampsia in pregnant mothers.

- Shams has also examined water resources using satellite data showing that changes in Total Water Storage from GRACE satellites reflects about a third surface water, a third soil water, and a third groundwater in Bangladesh.

- His analysis of GRACE data for global aquifers highlights interannual variability linked to wet and dry climate cycles that has been neglected in many other studies that focus on linear trends.

Shams is optimistic about future water resources and food security in Bangladesh if they continue with current groundwater pumping protocols (mostly in shallow zone) and apply the Bengal Water Machine in suitable areas to increase water availability for food production and reduce flooding from monsoons.

The Bengal Water Machine: Shamsudduha et al., 2022, Science